Anthroposophy, A Fragment

GA 45

I. The Character of Anthroposophy

Since ancient times, studying the human being has been felt to be the worthiest branch of human research. Yet, if we allow ourselves to be affected by all that is known about human beings—all the knowledge that has come to light throughout the ages—it is easy to become discouraged. Our questions about what a human being really is, and what our relationship to the universe is, are answered by a plethora of opinions and, as we ponder these opinions, we realize that they differ in manifold ways. As a result, we may feel that we are not called upon to undertake investigations of this sort and that we must give up hope of ever satisfying our desire to understand.

This feeling would be justified only if perceiving different views of an object were actually evidence that we are incapable of recognizing something true about that object. Those who accept this position would have to believe that no talk of knowledge or understanding is possible unless the complete nature of an object discloses itself to us all at once. But the human way of knowing is not such that the nature of things can be imparted all at once; it is more like painting or photographing a tree from a particular side. The picture gives the full truth of what the tree looks like from a certain point of view, but, if we select a different point of view, the picture becomes quite different. Only the combined effect of a series of pictures from various points of view can give an overall idea of the tree.

But this is the only way we can consider the things and beings of the world. We must necessarily state whatever we are capable of saying about them as views that hold true from different vantage points. This is the case not only with regard to observing things with our senses; it is also true in the spiritual domain—although we must not let ourselves be led astray by this comparison and imagine that differences in points of view in the latter have anything to do with spatial relationships. Every view can be a true view, if it faithfully reproduces what is observed. It is refuted only if it is proved to be legitimately contradicted by another view from the same perspective. That it differs with a view from a different perspective generally means nothing. Taking this position safeguards us against the insubstantial objection that in such a case every opinion must necessarily appear justified. When we see the tree from a specified vantage point, our image of the tree must have a particular shape; similarly, a spiritual view from a specified perspective must also have a particular form. It is clear, however, that we can demonstrate an error in a view only if we are clear on its perspective.

If we always kept this in mind, we would fare much better in the world of human opinions than is often the case. We would then realize that in many cases differences of opinion stem only from differences in perspective. Only by means of different but true views can we approach the essence of things. The errors that people make along these lines do not stem from individuals arriving at different views, but result from each person wishing to perceive his or her own view as the only justifiable one.

There is a readily available objection to all this. It could be said that, if we want to represent the truth, we should not merely provide one way of looking at the thing in question but should rather rise above all possible viewpoints to a holistic understanding. This may sound like a reasonable demand. However, it cannot possibly be met. What a thing is must be characterized from different points of view. The comparison to a tree that is painted from different perspectives seems relevant here. Someone who refuses to abide by these different views of the tree in arriving at an overall image might paint a very blurry, hazy picture, but there would be no truth in it. Similarly, truth cannot be gained from an understanding that seeks to encompass an object in a single glance, but only from putting together the true views resulting from different perspectives. This may not accommodate human impatience, but it does correspond to the realities we learn to recognize as we cultivate a richer striving for knowledge.

Little can lead us as firmly toward a real appreciation for the truth as such a striving for knowledge. This appreciation is rightly called real, because it cannot bring faint-heartedness in its wake. Because it recognizes the truth itself within truth's limitations, this appreciation does not lead us to despair of striving for truth. However, it does safeguard us against empty arrogance that believes that, in its own possession of the truth, it encompasses the full nature of things.

If we take these considerations sufficiently into account, we will find it understandable that we ought to strive for knowledge—especially knowledge of the human being—by attempting to approach the essence of our subject from different points of view. One such viewpoint—characterizable as lying midway between two others, as it were—has been chosen for what is being pointed to here. This is not to suggest that there are not many other viewpoints in addition to the three that we will consider. However, these three have been chosen as being especially characteristic.

The first point of view is that of anthropology. This science assembles what we can observe about human beings through our senses. Then, from the results of this observation, it attempts to draw conclusions about the essential nature of the human being. For example, it considers how our sense organs work, the shape and structure of our bones, the conditions that prevail in our nervous system, the processes involved when our muscles move, and so forth. Anthropology applies its methods to penetrating into the more subtle structure of our organs in an attempt to recognize the necessary conditions for feeling, conceptualization, and so forth. It also investigates similarities between human beings and animals and attempts to arrive at a concept of how human beings are related to other living things. It continues by investigating the living conditions of aboriginal peoples, who seem to have been left behind in evolution in comparison with the civilized nations. From these observations it develops ideas about what more developed peoples, who have passed the stage of development at which aboriginal peoples have remained, were once like. It investigates the remains of prehistoric human beings in the strata of the earth and formulates concepts about how civilization has progressed.

It investigates the influence of climate, the oceans, and other geographical conditions on human life. It tries to gain a perspective on the circumstances surrounding the evolution of the various races and ethnic lifestyles, on fights, the development of writing and languages, and so forth. In this context, we are applying the name "anthropology" to the totality of our physical studies of the human being, including not only what is often attributed to it in the narrower sense of the word, but also human morphology, biology, and so on.

As a rule, anthropology stays within the currently recognized limits of the scientific method. It has accumulated a monumental amount of information, and the ways of thinking applied in summing this up differ considerably. In spite of this, anthropology has a very beneficial contribution to make to our understanding of human nature, and it is constantly adding new information. In accord with our modern way of looking at things, great hopes are placed on what anthropology can do to shed light on the human conundrum. It goes without saying that many people are as confident of anthropology's point of view as they are doubtful of the viewpoint to be described next.

This second point of view is that of theosophy. It is not our intention here to explore whether the choice of this Word is fortunate or unfortunate; we shall simply use it to designate a second perspective on the study of human beings that is in contrast to that of anthropology.

Theosophy presupposes that human beings are, above all, spiritual beings and attempts to recognize them as such.1See "alternate version" below for another version of the rest of this chapter. It sees the human soul, not only as "mirroring" and assimilating sense-perceptible things and processes, but also as capable of leading a life of its own, a life that receives its impetus and content from what can be called the spiritual side. It refers to human beings as capable of entering spiritual as well as sense-perceptible domains. In the latter, our knowledge and understanding expand as we direct our senses to more and more things and processes and form concepts based on them. In the spiritual domain, however, acquiring knowledge takes place differently; there, the observing is done within our inner experience. A sense-perceptible object stands there in front of us, but a spiritual experience rises up from within us, as if from the very center of our individual being.

As long as we cherish the belief that this is simply something taking place within the soul itself, theosophy must indeed seem highly questionable, since this belief is not at all far from the belief that presupposes such experiences to be nothing more than a further distillation of what we have observed through sense perception. To persist in such a belief is possible only as long as we have not had compelling reasons to be convinced that, after a certain point, inner experiences, just like sense-perceptible facts, are in fact determined by a world external to the human personality. When this conviction is acquired, the existence of a spiritual "outer world" must then be recognized, just as we recognize a physical one. It will then become clear to us that, just as we are rooted in a physical world through our physical nature, we are related to a spiritual world through our spiritual nature. We will then find it comprehensible that information can be gathered from this spiritual world to help us understand the spiritual human being, just as anthropology gathers information through physical observation to understand the physical human being. We will then no longer doubt the possibility of researching the spiritual world.

Spiritual researchers transform their soul experience in such a way that the spiritual world can enter it. They shape certain inner experiences so that the spiritual world reveals itself in them. (How this happens is described in my book How to Know Higher Worlds.) Thus configured, soul life can then be described as "clairvoyant consciousness". This is not in any way to be confused with the plethora of current shady practices that also go under the heading of "clairvoyance."

Coming to inner experience in such a way that one or another fact of the spiritual world can reveal itself directly to the soul requires much time, self-denial, and inner effort on the part of the soul. However, it would be a fatal preconception to believe that these soul experiences can bear fruit only for those individuals who achieve direct experience through inner exertion of this sort. That is not the case. Once spiritual facts have come to light in this way, they have been "conquered" for the human soul. If the spiritual researcher who has discovered them communicates them to others, they can then become clear to any individual who listens with impartial logic and a healthy sense for the truth. We should not believe that a well-founded certainty in the facts of the spiritual world is possible only for clairvoyant consciousness. Each and every soul is attuned to recognize the truth spiritual researchers have discovered. If a spiritual researcher makes claims that are untrue, impartial logic and a healthy sense of truth will recognize this and reject them.

Directly experiencing spiritual knowledge requires complex inner paths and practices, but possessing this knowledge is indispensable for any soul desiring to be fully conscious of its humanity. Without such consciousness, a human life is no longer possible after a certain point in our existence.

Although theosophy is capable of supplying knowledge that satisfies the most important needs of the human soul, and although this knowledge can be recognized by a healthy sense of truth and sound logic, there will always be a certain gap between theosophy and anthropology. The possibility will always exist that we will be able to demonstrate theosophy's conclusions regarding the spiritual nature of the human being and then indicate how anthropology confirms everything theosophy says. But the road between one domain of knowledge and the other will be a long one.

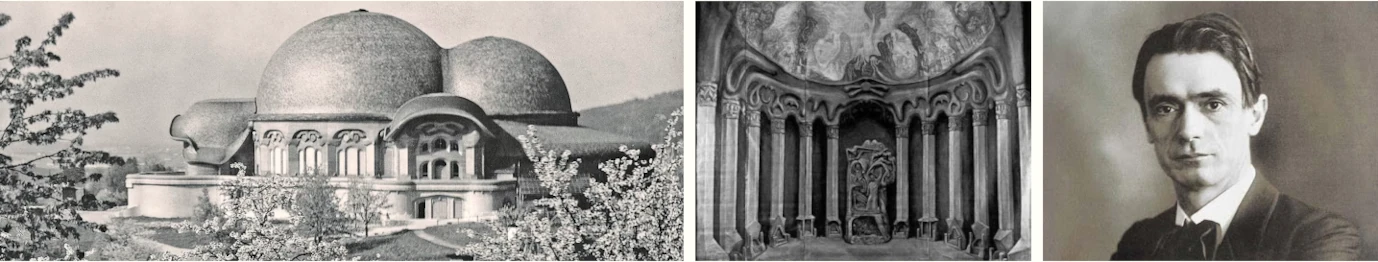

It is, however, possible to fill in the gap. This can be seen as the aim of the following sketch of an anthroposophy. If anthropology can be likened to the observations of a traveler in the lowlands who gets an idea of the character of an area by going from place to place and house to house, and if theosophy can be likened to the view we get of the same area from the top of a hill, then anthroposophy can be likened to our view from the slope of the hill, where we still see all the various details, but they begin to come together to form a whole.

Anthroposophy will study human beings as they present themselves to physical observation, but in the practice of this observation it will try to derive indications of a spiritual foundation from the physical phenomena. In this way, anthroposophy can make the transition from anthropology to theosophy.

It should be expressly mentioned that only a very brief sketch of anthroposophy can be given here, as a detailed description would entail too much. This sketch is intended to consider the human being's bodily nature only inasmuch as it is a revelation of the spiritual. This is what is meant by anthroposophy in the narrower sense. This would then have to be accompanied by psychosophy, which studies the soul, and by pneumatosophy, which is . concerned with the spirit. With that, anthroposophy leads over into theosophy itself.2For this progression, see The Wisdom of Man, of the Soul, and of the Spirit, which was previously called Anthroposophy, Psychosophy, and Pneumatosophy.

Alternate version

Theosophy presupposes that human beings are, above all, spiritual beings and attempts to recognize them as such. For theosophy, the life that a human being leads in different circumstances, climates, or times is a revelation of the spiritual being. Theosophy attempts to recognize the different forms in which this spiritual being can reveal itself and to portray out of the spirit what anthropology seeks to understand through outer observation. Theosophy's view of this spiritual being is not put forth as an arbitrary claim. Like anthropology, it is based on facts, although, because of their nature, these facts are contested from many quarters. Theosophy speaks of the inner aspect of the human being as something that can be developed; it is not something fixed and finished. Theosophy sees this inner aspect as containing seeds that can begin to sprout. When they do, we do not merely experience inner realities but enter into a world that is no less external to us than the sense-perceptible world. Our inner experiences begin to transmit this external spiritual world to us. They are not an end in themselves but are the means by which we go from our own inner world to the outer world of the spirit, just as our senses are the means by which the sense-perceptible outer world becomes our inner soul world.

Naturally, our relationship to the spiritual outer world must be different from our relationship to the sense-perceptible one, whose essential form always presents itself to us in the same way, regardless of how we approach it. What goes on in our inner world can in no way change the course of sense-perceptible reality. Things are completely different, however when our inner life is meant to develop into an organ for observing the spiritual world. First of all, we must silence any personal whims. This requires quite specific prerequisites. Inasmuch as these prerequisites achieve the necessary degree of perfection only approximately, individuals will always have difficulty in coming to a consensus on what they experience in the spiritual world by developing their inner life. Spiritual researchers cannot reach an agreement as easily as scientists of the physical world can. This, however, does not change the fact that we can develop inner dormant seeds into organs that lead us into a spiritual world. Only those who refuse to acknowledge this fact will raise objections to research into the spiritual world on the basis that spiritual researchers do not agree with each other.

Thus, theosophy is based on inner human experiences. Once such experiences have been discovered by one human soul, they can be understood by all others who do not totally shut themselves off from understanding. There is a string that can then resonate with anything a more highly developed soul may experience. This means that the spiritual world is just as much a matter for communication from person to person as the sense-perceptible world is. Because sense-perceptible realities present themselves in the same way to the unbiased observation of all, agreement about them must prevail. Agreement on a reality in the spiritual world cannot be brought about by outwardly taking people to look at something, but agreement will always result among individuals who follow inner soul paths to the spiritual reality in question. Those who actually follow this soul path, and are furthermore concerned only with the truth, will not be confused by what different spiritual researchers may say. They know that the contradictions are all too easily explained by the difficulties that arise when all personal whims must be eliminated.

It is understandable that theosophy's point of view seems questionable to many people. As it appears in the cultural evolution of humanity, it rises above the experiences of immediate existence to highlights of spiritual research. Although those individuals who need the results of theosophy to experience satisfaction in life will greet it with profound interest, others will be of the opinion that it is impossible for human beings to develop capacities to reach such heights. While there are doubtless many paths linking the results of spiritual research to our immediate life, it is also true that these paths are long for those who are conscientious. That is why what theos¬ophy has to say about the human being seems so distant in many respects from the conclusions of anthropology.

In what follows, a third point of view will be taken up, standing midway between anthropology and theosophy. The resulting perspective will be called anthroposophy. Unlike theosophy, it will not present the results of inner experiences directly and will not see the external aspect of the human being as a manifestation of what is spiritually human; rather, this manifestation itself is what we will have in view. We will observe the external nature of the human being living in the sense-perceptible world, but in doing so we will seek out the spiritual foundation by means of its manifestation. We will not, however, stop with describing the manifestation as it manifests in sense-perceptible reality, as anthropology does. If theosophy could be likened to standing on top of a mountain surveying the landscape, while anthropology is investigating down in the lowlands, forest by forest and house by house, then anthroposophy will choose its vantage point on the slope of the mountain, where individual details can still be differentiated but integrate themselves to form a whole.

Only a brief sketch of a science characterized in this way will be given here; almost everything will appear as no more than suggestions. In the not-too-distant future, two other sketches will be added to form a totality with this one. In what follows, only what relates to the bodily nature of the human being will be depicted. This is what will be called anthroposophy in the narrower sense. A second sketch dealing with the soul will be called psychosophy, while the third, dealing with the spiritual aspect of the human being, will be called pneumatosophy. With that we Will arrive at the conclusions of theosophy, although by a different path than that taken by theosophy itself.